Early in the morning of April 25, 1986, nuclear engineer Alexander Akinhov was busy preparing his night-shift team for a special test they were about to conduct at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant #4 in northern Ukraine. The team was trying to see how an emergency water cooling system would work in the event of a complete loss of power at the plant. The plant’s backup diesel generators had never been able to get up to full speed quickly enough to power the coolant pumps needed to cool the reactor in the event of a power failure. So, the idea was that maybe the plant’s steam turbine could be used to generate enough electric power to run the plant’s coolant pumps for the 45 seconds needed until the diesel generators could fully kick in. Three earlier tests had been carried out at the plant since 1982 but none had been successful. Each time, the system was modified in some way. This time, Akinhov and his team were hoping for success.

Early in the morning of April 25, 1986, nuclear engineer Alexander Akinhov was busy preparing his night-shift team for a special test they were about to conduct at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant #4 in northern Ukraine. The team was trying to see how an emergency water cooling system would work in the event of a complete loss of power at the plant. The plant’s backup diesel generators had never been able to get up to full speed quickly enough to power the coolant pumps needed to cool the reactor in the event of a power failure. So, the idea was that maybe the plant’s steam turbine could be used to generate enough electric power to run the plant’s coolant pumps for the 45 seconds needed until the diesel generators could fully kick in. Three earlier tests had been carried out at the plant since 1982 but none had been successful. Each time, the system was modified in some way. This time, Akinhov and his team were hoping for success.

At 1:23:04 am, the experiment began. Steam to the plant’s turbines was shut off and the emergency diesel generator started per plan. But 36 seconds into the test something began to go horribly wrong. The system’s steam turbine generator was slowing as was planned but the system began allowing more water to be converted to steam to increase power. The plant’s automated control system then began to insert control rods into the reactor core to limit the power rise. But it was too late. For Akinhov it was one of those “Oh crap” moments. Even before steam levels grew to explosive levels within the plant, it’s now believed that a series of nuclear explosions occurred 53 seconds after the experiment began. These sent a plume of debris almost two miles into the air. Three seconds later, the steam buildup ruptured the reactor, blew the top off the building and sent even more radioactive material airborne. And so began the greatest nuclear power plant catastrophe in history. Akinhov immediately reports, “The reactor is OK, we have no problems.” He later dies from radiation sickness.

The hot debris from the explosions set part of the complex on fire and the fire department arrived 20 minutes later. The firefighters, unaware of the escaping radiation, headed straight into the area, unprotected, to fight the fires. The next day, the nearby town of Prypiat was ordered to be evacuated. Busses took the 40,000 residents away to Kiev on short notice with only what they could carry. Meanwhile the radioactive cloud spread north to Belarus and west, covering most of Ukraine, Poland and over Germany and France. Three days later, Moscow was aware of the extent of the catastrophe but agreed that the annual May Day parade in Kiev go on as scheduled to avoid panic and to assure people that there is no danger. Thousands of people were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. The full extent of the tragedy and the cost of its containment eventually lead to the collapse of the Soviet Union, three years later.

Today, after 32 years, the effects of the released radiation are still being seen. 31 people died within a few days of the accident but no one really knows how many were affected. Estimates range from 10,000 on the low end to over 100,000 on the high end. Belarus, absorbed an estimated 70% of the nuclear fallout and has experienced a sharp rise in birth defects since 1986. For anyone, the long-term effects of radiation exposure are a sobering reminder of how terrible nuclear radiation can be.

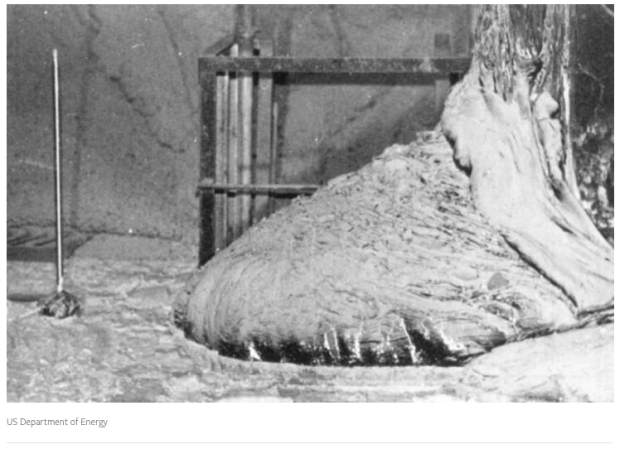

In the years immediately after the disaster, the Soviets built a somewhat primitive concrete tomb, called a sarcophagus, to cover the reactor. This sarcophagus will eventually deteriorate and a larger new containment structure is now finally nearing completion over the remains of the reactor. Radiation from the reactor will continue for the next 100,000 years and the area around the plant probably won’t be safe for people to live for at least 20,000 years. Here is a photo of the actual nuclear material taken 10 years after the accident. It’s actually a mixture of molten nuclear material combined with concrete and debris.

So this place sounded like just the right kind of destination for our intrepid twosome. Guided tours make the full-day trip from Kiev regularly and Tanya and Jay wanted to see this place first-hand. Eight other travelers joined them, along with a guide and driver, in a van whose shock absorbers had seen better days. The Chernobyl power complex is actually made up of four reactors, including the damaged reactor #4. The other three have all been shut down and are undergoing the long-term process of de-commissioning. The complex is surrounded by a closely guarded 30-kilometer “exclusion zone” where visitors are carefully checked in and out and are required to pass through two different radiation detector stations as they exit. Everyone in T and J’s group was issued hand held detectors which all started beeping wildly whenever especially contaminated areas were approached.

The tour consisted of four primary sites: the town of Chernobyl, the reactor complex, a nearby village and the abandoned town of Prypiat which was closest to the accident. Chernobyl town is about 7 km from the reactor complex and now serves principally as a housing and support services area for workers de-commissioning the power plant. Employees work 15 days at a time, then leave the area for another 15 days before returning.

Visitors are allowed no closer than 300 meters from the nearly-completed containment structure and for some reason photos are not allowed to be taken, but we got some anyway.

The eeriest part of the day was walking around the abandoned town of Prypiat. This town, built in 1970 served as a model Soviet community for the 40,000 people associated with the nuclear plant. Schools, cafeteria, apartment blocks, movie theatre and hotel were all part of what the Soviets wanted to portray to the outside world as life in the progressive USSR. It’s pretty much been left as it was when it was abandoned right after the accident. The amusement park area was scheduled to open just a few weeks after the disaster.

Since 1986, some of the buildings have simply collapsed due to the elements and poor initial construction.

Some people, who were not fortunate enough (or not) to live in Prypiat lived in a few nearby villages. These folks were evacuated later and left behind the remains of their homes, school, grocery store and kindergarten/nursery.

After several hours exploring areas within the exclusion zone, our van driver and guide took the group 5 kilometers down a lonely single lane road to one of the weirdest places our gruesome twosome had ever visited, the abandoned Cold War relic, Radar Duga-1. This was a huge super-secret antennae system build by the Soviets in 1976 as an early warning to track potential incoming US missiles. This thing was like something straight out of the X-Files. The cover story was that the road leading to the antennae was the entrance to a boy scout camp, but it’s hard to believe anyone nearby would ever buy that idea. Duga-1 sent out extremely powerful radio signals, which unfortunately disrupted commercial broadcasts, aviation communications and amateur radios resulting in complaints from several countries. Some speculated that Duga-1 was designed for Soviet weather control or mind control experiments but NATO intelligence figured out pretty quickly what Duga’s real purpose was, as well as determining pretty accurately where the antennae was located. It was shut down in 1989 when the Soviet Union collapsed.

The day ended with not only a reminder of the colossal waste of preparing for nuclear conflict but also a somber reminder of the people who suffered so terribly as a result of the worst nuclear power plant accident in history.

The roughly six-hour ride in a sleeper compartment on Ukraine Railways was very pleasant and our traveling tramps arrived in Lviv, refreshed and ready to take on the next day.

The roughly six-hour ride in a sleeper compartment on Ukraine Railways was very pleasant and our traveling tramps arrived in Lviv, refreshed and ready to take on the next day.

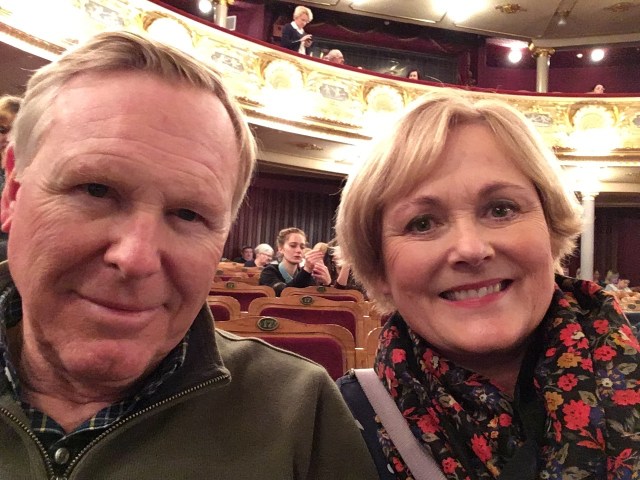

The gem of Lviv’s downtown is its opera house, modeled after the State Opera House in Vienna.

The gem of Lviv’s downtown is its opera house, modeled after the State Opera House in Vienna.

Notice the female figure adorning the top of the opera house. Does she look a bit pregnant?

Notice the female figure adorning the top of the opera house. Does she look a bit pregnant?  Well, she is. It seems that that sculptor who created the work, “Glory” used as his model a woman who was about four months pregnant and the statue was made accordingly. Our two culture vultures snagged two tickets for a performance of Puccinni’s “Madame Butterfly”. At $12 a ticket, it was worth every penny, or hryvnia.

Well, she is. It seems that that sculptor who created the work, “Glory” used as his model a woman who was about four months pregnant and the statue was made accordingly. Our two culture vultures snagged two tickets for a performance of Puccinni’s “Madame Butterfly”. At $12 a ticket, it was worth every penny, or hryvnia.

After you’re seated, this big guy in an quasi-torturer’s outfit comes by, sizes you up and decides whether you deserve punishment.

After you’re seated, this big guy in an quasi-torturer’s outfit comes by, sizes you up and decides whether you deserve punishment.  After he’s selected some volunteer for retribution, the poor sucker is placed in a cage and then lowered into “the pit” where he stays until he either begs for mercy or the torturer has decided he’s had enough. The whole thing is mildly entertaining and, of course, kind of weird.

After he’s selected some volunteer for retribution, the poor sucker is placed in a cage and then lowered into “the pit” where he stays until he either begs for mercy or the torturer has decided he’s had enough. The whole thing is mildly entertaining and, of course, kind of weird.

The University was once the residence of the Bukovinian and Dalmation Metropolitans (Church Bishops) and still includes the impressive Seminarska Church. Away from the university, one is never far from a church, like the St. Nicholas Cathedral, nicknamed the “drunken church” because of its twisted turrets.

The University was once the residence of the Bukovinian and Dalmation Metropolitans (Church Bishops) and still includes the impressive Seminarska Church. Away from the university, one is never far from a church, like the St. Nicholas Cathedral, nicknamed the “drunken church” because of its twisted turrets.

The beauty of these buildings often stands in stark contrast to the much of the rest of the city, which is more of a reminder of its not so distant Soviet past.

The beauty of these buildings often stands in stark contrast to the much of the rest of the city, which is more of a reminder of its not so distant Soviet past.

Two weeks in Ukraine in November left lasting impressions on our traveling duo. This is a country with an incredibly complex and sad past, an uneasy present and an uncertain future (as if the future is ever certain). To say these people have been through a lot in the last 100 years is an understatement. Think mass starvation under Stalin in 1932-33 to the tune of 10 million people, invasion by Nazi Germany in 1941 followed by some of the fiercest fighting of World War II and the subsequent slaughter of thousands of Poles and Jews by Ukrainian partisans. Add to this mix, the joys of living as part of the post-war Soviet Union and, oh yes, having part of your country contaminated by the world’s largest nuclear power plant accident at Chernobyl in 1986. Then, of course, you have the political turmoil of the last 13 years where corruption is the rule and Russia unilaterally annexes part of your country, Crimea, and you lose several thousand people fighting the Russians on your eastern border and have to deal with about half a million displaced people as a result. Depressed yet?

Two weeks in Ukraine in November left lasting impressions on our traveling duo. This is a country with an incredibly complex and sad past, an uneasy present and an uncertain future (as if the future is ever certain). To say these people have been through a lot in the last 100 years is an understatement. Think mass starvation under Stalin in 1932-33 to the tune of 10 million people, invasion by Nazi Germany in 1941 followed by some of the fiercest fighting of World War II and the subsequent slaughter of thousands of Poles and Jews by Ukrainian partisans. Add to this mix, the joys of living as part of the post-war Soviet Union and, oh yes, having part of your country contaminated by the world’s largest nuclear power plant accident at Chernobyl in 1986. Then, of course, you have the political turmoil of the last 13 years where corruption is the rule and Russia unilaterally annexes part of your country, Crimea, and you lose several thousand people fighting the Russians on your eastern border and have to deal with about half a million displaced people as a result. Depressed yet?

September and the early part of October found us back in the Homeland, immersing ourselves in visits with friends, family and jazz. Other than a week in Monterey, California for our annual visit to the Monterey Jazz Festival, all our time was spent in Oregon and it was good to be back in familiar territory.

September and the early part of October found us back in the Homeland, immersing ourselves in visits with friends, family and jazz. Other than a week in Monterey, California for our annual visit to the Monterey Jazz Festival, all our time was spent in Oregon and it was good to be back in familiar territory.

On our trip back to the homeland, Tanya and Jay simply could not resist visiting the Oregon State Fair. For our readers outside the US, who may not be familiar with state fairs, they are a bit of a throwback to the time when America was much simpler, less-populated and more agrarian. Every state has at least one annual state fair and Oregon’s is held at the end of every summer in the state capital, Salem.

On our trip back to the homeland, Tanya and Jay simply could not resist visiting the Oregon State Fair. For our readers outside the US, who may not be familiar with state fairs, they are a bit of a throwback to the time when America was much simpler, less-populated and more agrarian. Every state has at least one annual state fair and Oregon’s is held at the end of every summer in the state capital, Salem.

Housed in a nondescript white building that looks like it was a church at one time, are the remains of and artifacts taken from three Viking sailing ships, two of which are the best preserved in the world. These ships were unearthed between 1850 and 1904. All had been previously at sea but were used as burial chambers for high-ranking Vikings. Before being buried, the ships were filled, not only with the deceased Viking corpse, but with jewelry, clothing, furniture, tools, servants, cows and horses to be used in the afterlife.

Housed in a nondescript white building that looks like it was a church at one time, are the remains of and artifacts taken from three Viking sailing ships, two of which are the best preserved in the world. These ships were unearthed between 1850 and 1904. All had been previously at sea but were used as burial chambers for high-ranking Vikings. Before being buried, the ships were filled, not only with the deceased Viking corpse, but with jewelry, clothing, furniture, tools, servants, cows and horses to be used in the afterlife.

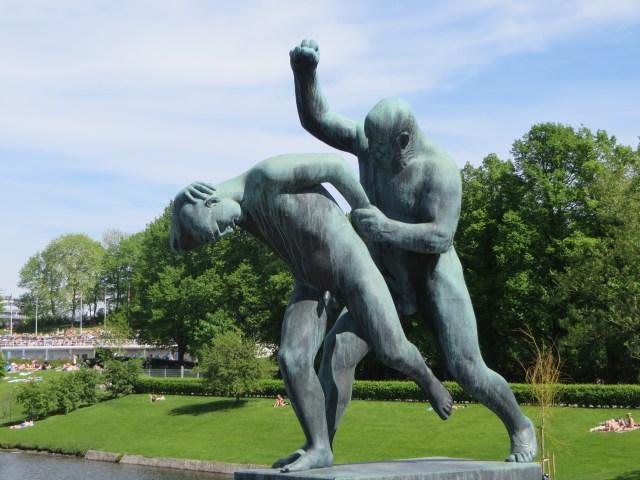

We then went on to the second example of the Norwegian mindset: Vigeland Park. This park is part of the larger Frognerpark, slightly northwest of city center Oslo. The park features large grassy expanses, and on this sunny Saturday afternoon, was filled with people enjoying picnics and soaking up the sun. Not exactly an example of suffering, except given the fair Norwegian skin there would no doubt some sunburn suffering the following day.

We then went on to the second example of the Norwegian mindset: Vigeland Park. This park is part of the larger Frognerpark, slightly northwest of city center Oslo. The park features large grassy expanses, and on this sunny Saturday afternoon, was filled with people enjoying picnics and soaking up the sun. Not exactly an example of suffering, except given the fair Norwegian skin there would no doubt some sunburn suffering the following day.

But, Jay sees Vigeland’s work as an appropriate manifestation of “Norwegianness”, that is struggling and doing things the hard way. The work and messages Vigeland put into carving these figures from granite can be compared to the struggles and suffering of the Vikings. If there is no struggle and hardship, what use is the victory? This is what defines being Norwegian. It also partially explains the guilt and uneasiness many Norwegians feel about the wealth of recent decades as a result of North Sea oil drilling and how this “easy money” has affected their traditional way of life. But that could be the subject of another posting.

But, Jay sees Vigeland’s work as an appropriate manifestation of “Norwegianness”, that is struggling and doing things the hard way. The work and messages Vigeland put into carving these figures from granite can be compared to the struggles and suffering of the Vikings. If there is no struggle and hardship, what use is the victory? This is what defines being Norwegian. It also partially explains the guilt and uneasiness many Norwegians feel about the wealth of recent decades as a result of North Sea oil drilling and how this “easy money” has affected their traditional way of life. But that could be the subject of another posting. The castle was built in the 1420’s and Shakespeare wrote Hamlet in 1601. But, Shakespeare never visited Denmark and apparently only heard about the castle from traveling musicians who had been there “on tour”. This, of course, has not stopped the local chamber of commerce from capitalizing on the Hamlet setting and every August the Shakespeare Festival is presented, with open-air performances held at the castle.

The castle was built in the 1420’s and Shakespeare wrote Hamlet in 1601. But, Shakespeare never visited Denmark and apparently only heard about the castle from traveling musicians who had been there “on tour”. This, of course, has not stopped the local chamber of commerce from capitalizing on the Hamlet setting and every August the Shakespeare Festival is presented, with open-air performances held at the castle.

And, who says the Danes don’t have much of a sense of humor? Check out these examples seen while walking across the bridge to the castle.

And, who says the Danes don’t have much of a sense of humor? Check out these examples seen while walking across the bridge to the castle.

From the outside, one would think this would be a very busy and bustling station. In fact, there are only six tracks, five platforms and you have to buy your train ticket from the 7-Eleven store inside the building. Still, the station is historically protected, and there are several scheduled arrival/departures throughout the day, making Helsingør a great day trip from Copenhagen.

From the outside, one would think this would be a very busy and bustling station. In fact, there are only six tracks, five platforms and you have to buy your train ticket from the 7-Eleven store inside the building. Still, the station is historically protected, and there are several scheduled arrival/departures throughout the day, making Helsingør a great day trip from Copenhagen. There’s one main road running through town and a secondary street, shown here, that parallels it. Sevnica supports itself through agriculture, its underwear factory and as a base for hikers and outdoor enthusiasts. Getting there involves taking sometimes narrow country roads, often heavily used by tractors and farm equipment. Other than being the childhood home of Melania, its other primary claim to fame is its ancient Sevnica Castle, now housing a museum, event rooms and a sandwich and gift shop.

There’s one main road running through town and a secondary street, shown here, that parallels it. Sevnica supports itself through agriculture, its underwear factory and as a base for hikers and outdoor enthusiasts. Getting there involves taking sometimes narrow country roads, often heavily used by tractors and farm equipment. Other than being the childhood home of Melania, its other primary claim to fame is its ancient Sevnica Castle, now housing a museum, event rooms and a sandwich and gift shop.

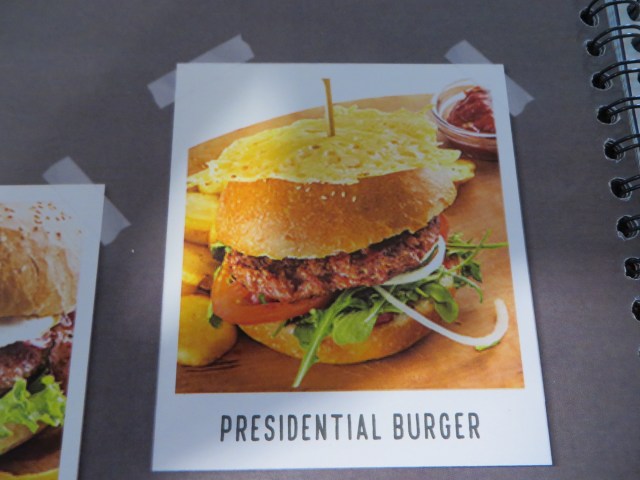

Later, we had lunch at a local joint which featured the “Presidential” burger, which also must have appeased the lawyers, who either missed, or just didn’t care about the whimsical, if not cheeky, inclusion of a piece of dried cheese ornamenting the top of the burger bun.

Later, we had lunch at a local joint which featured the “Presidential” burger, which also must have appeased the lawyers, who either missed, or just didn’t care about the whimsical, if not cheeky, inclusion of a piece of dried cheese ornamenting the top of the burger bun.

But the tourist office was hoping we would take time to not only see all things Melania but also to visit the local castle and spend time in Sevnica to enjoy a hiking holiday.

But the tourist office was hoping we would take time to not only see all things Melania but also to visit the local castle and spend time in Sevnica to enjoy a hiking holiday.